A friend just emailed asking what to do with a professional colleague who can’t get a job. A talented guy, he likes to blog and tweet against about political correctness and coddled minorities. He thinks “diversity” is a form of bigotry, women can’t take a joke, and “anchor babies” sneer at the 14th amendment. All this would probably get him a shot at the White House. But he’s not applying for that job.

My pal spent hours trying to help him. “His career is in a tailspin, but he won’t accept the fact that all his outbursts on social media are a big reason.” Finally, my friend gave up. “What would you have done?” he asked.

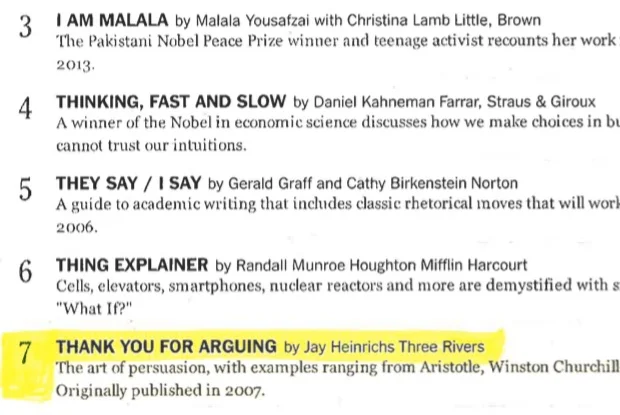

As someone who writes books on persuasion, I often get asked about political friends—people who take the First Amendment as a license to be rude. Actually, it is; you have the constitutional right to hurt people’s feelings. But other people have the right to think you’re a jerk, even when you’re not. Hardly a great qualification for employment.

Here’s what I try to explain to people who think they should say whatever they want and that the world should hire them anyway.

It’s still a free country.

Employers reasonably want to avoid spending five days a week working with an overly opinionated person, especially one who might be bad for business.

Every job application is a sales job.

To sell anything—including yourself—you need to persuade. That means starting with your audience’s beliefs and expectations, and using those beliefs to guide them toward the choice you want.

Persuasion starts with fitting in.

A guy who hurts the feelings of people he may end up working with—including African Americans, Hispanics, and women—probably won’t fit in. Geek alert: the Latin for “fitting in” is decorum. In rhetoric, the art of persuasion, decorum means being suited to your environment. It’s like planting a rubber tree in the Sahara. The tree will fail to fit in, and so it will die. If you tweet objectionable things about people you’re trying to work with, you’re a rubber tree.

This isn’t about rights. It’s about your career drying up.

But wait, you’re not racist or sexist!

Good for you. The problem is, persuasion is all about what your audience thinks. If an employer finds you a jerk, saying “I’m not an jerk” will probably fail to persuade her.

There’s political correctness, and then there’s being rude.

People who yell at you for eating the wrong fish in a restaurant are being rude. Similarly, people who have a hissy fit when you wish them a happy holiday instead of the conservatively correct “Merry Christmas” are also being rude.

The rules change over time and with different groups. In 1939, when my mother saw “Gone with the Wind,” the audience was shocked at Rhett Butler’s “Frankly, my dear, I don’t give a damn.” Cursing in a movie! But then, my mother had to sit in the balcony because the family’s African-American cook had brought her: no “Negroes” allowed in the good seats.

Society gets ruder in some ways, more polite in others. Call these changing rules “political correctness” if you want. But to get a job, you need to know the rules of employers. Go ahead and say whatever truths pop up in your head. But don’t expect to be rewarded with a job.

No, free speech isn’t dead.

Nobody is going to prosecute you for being a jerk on social media. So here’s what I would say to my friend’s colleague: “Hey, I admire you for standing up for your principles. You’re a real martyr for your cause!”

And then I’d remind him that McDonald’s is hiring.